Just a quick follow up from research done after reading How To Survive A Garden Gnome Attack. The author's blog had a link to some live footage of an attack on some police man. Go ahead and skip to about 0:40. And you thought it was a joke, didn't you?

Thursday, September 27, 2012

Monday, September 24, 2012

The Checklist Manifesto

I checked out The Checklist Manifesto, by Atul Gawande, as part of an attempt to get my life more organized and better prioritized. (Let's just say I overcommitted a bit last spring.) I also have a tendency to write down too many items on my todo lists, and they can lose their usefulness quickly. I was hoping this would help me to use checklists more effectively.

I was wrong. Well, mostly. It turned out to be an argument for *doctors* to use checklists much more regularly in their operations, largely surgeries, in order to avoid forgetting to do obvious things. As it turns out, there is a need:

"In 2001, [a previous checklist study was performed]. Doctors are supposed to (1) wash their hands with soap, (2) clean the patient's skin with chlorhexidine antiseptic, (3) put sterile drapes over the entire patient, (4) wear a mask, hat, sterile gown, and gloves, and (5) put a sterile dressing over the insertion site once the line is in. Check, check, check, check, check. These steps are no-brainers; they have been known and taught for years. So it seemed silly to make a checklist for something so obvious. Still, Pronovost asked the nurses in his ICU to observe the doctors for a month as they put lines into patients and record how often they carried out each step. In more than a third of patients, they skipped at least one."

(pages 37-38, emphasis mine)

Yikes.

All very basic stuff huh? As a patient, I just kind of assume that these things are happening behind the scenes and that they'd never make a mistake as simple as forgetting to wash their hands. Evidently not.

In the next year the nurses were encouraged to correct the doctors when they witnessed steps being skipped. "The results were so dramatic that they weren't sure whether to believe them: the ten-day line-infection rate went from 11 percent to zero." (page 38) An estimated eight lives saved in one hospital, from making sure medical professionals remembered to sterilize everything!

Gawande then goes on to describe how checklists are used successfully in other fields, and this was surprisingly interesting as well. For example, construction of large buildings/skyscrapers is evidently done by breaking the design into multiple subsystems, and each team effectively has a giant checklist they're working through. And to make sure the different teams work nicely with each other, some of the tasks are communication-oriented, e.g. have a cross-team meeting to discuss potential issues after the water lines are put in. Gawande is advocating a similar approach in medicine; instead of having one exalted physician or surgeon, maybe we should entrust our health to multiple experts and attempt to do a better job communicating amongst themselves.

Aviation was presented as the gold standard in checklists. Evidently pilots have manuals which consist of hundreds of checklists on the plane every time they fly. Most are never used, but they'll describe every possible disaster scenario and the really obvious first steps that must be performed. One objection readers may have here and elsewhere is that in a crisis scenario the expert should be free to perform by intuition and not be restricted by red tape. Gawande would disagree, to a point. "The [airline] checklists have proved their worth--they work. However much pilots are taught to trust their procedures more than their instincts, that doesn't mean they will do so blindly. Aviation checklists are by no means perfect ... You want to keep the list short by focusing on what he called 'the killer items'--the steps that are most dangerous to skip and sometimes overlooked nonetheless." (pages 121, 123) And they must be short, in the 5-10 item, ~30 second range. At this point, the argument goes, you've removed the costliest, most frequent mistakes and it's time to let the experts act on their own and amaze us.

Gawande also believes that this line of reasoning could be extended to just about anything. Like investing - did you actually read Company X's cashflow statement before buying its stock? But I was a bit disappointed it wasn't more practical on a personal level. There are things that fit into this approach, like remembering to pay the credit card bill, but my life is less ... procedural ... than things in this book.

But it was still a fascinating book. Sometimes I amaze myself at the variety of things I can make myself interested in. To be fair, this wasn't the first medical book I've read and enjoyed, but it probably was the first analysis of construction that's been written interestingly enough to hold my attention! And in case you were wondering, Gawande did ultimately come up with a three-part, nineteen item checklist for use in surgeries that has performed well in testing so far. It's also been winning many converts from skeptical doctors who usually think a bit too highly of themselves and see it as a waste of time, until the checklist saves someone from a (literally) deadly mistake! Here's a sample of the current checklist:

"Before anesthesia, there are seven checks. The team members confirm that the patient (or the patient's proxy) has personally verified his or her identity and also given consent for the procedure. They make sure that the surgical site is marked and that the pulse oximeter--which monitors oxygen levels--is on the patient and working. They check the patient's medication allergies. They review the risk of airway problems--the most dangerous aspect of general anesthesia--and that appropriate equipment and assistance for them are available. And lastly, if there is a possibility of losing more than half a liter of blood (or the equivalent for a child), they verify that necessary intravenous lines, blood, and fluids are ready." (page 140)

Maybe our next visits will be just a little bit safer :)

4.5/5 - I might actually purchase this one someday

Review also posted to LibraryThing

Thursday, September 13, 2012

I Judge You When You Use Poor Grammar

There were some amusing bloopers - such as 'YEILD' written in official large lettering on a road, a 'DONT'T DRINK AND DRIVE' road sign, or a typo on an immigration form, but overall it just wasn't as exciting as it could've been with some more variety.

2.5/5 stars

Review also posted on LibraryThing

Friday, September 7, 2012

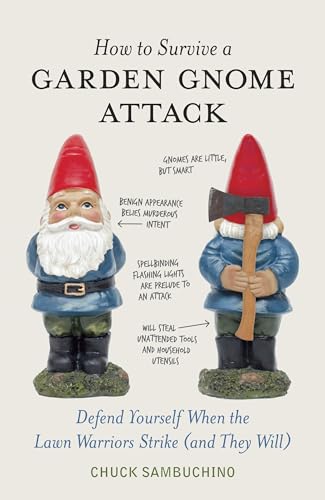

How To Survive A Garden Gnome Attack

This

was a nice quick read a couple weeks ago. It only took me two days,

start to finish, which, the way I read and rotate through books, is

amazingly fast. In part it was because it was short, only about 100

pages, and many of them had large pictures. More importantly, it was

just too amusing to put down. The premise is that gnome attacks are a

widespread, undiscussed problem, and this is the definitive survival

manual. The author advocates, among other things, digging moats and

placing quicksand (recipe provided - it needs maple syrup!) around your

house to trap any approaching gnomes. Once captured, the best way to

"dispose" of them is to encase them in concrete...

I'm sure there are very similar books out there for zombie attacks, but this was the first I had heard dealing with gnomes. I wonder if there's a gnome subculture out there as there is for zombies, but I suspect not. The author has evidently been asked many times where he got the idea (hey, that's exactly what my dad was asking as I read it!), and he answers that it was a snapshot of a movie that creeped him out. So I suspect he made it up. He also has an amusing blog on the subject over here.

I kinda want to buy a garden gnome now. Since my sister also read this, it could "appear" in various places to scare her!

4/5 stars for pure creativity; probably won't buy it, but it was worth a read

I'm sure there are very similar books out there for zombie attacks, but this was the first I had heard dealing with gnomes. I wonder if there's a gnome subculture out there as there is for zombies, but I suspect not. The author has evidently been asked many times where he got the idea (hey, that's exactly what my dad was asking as I read it!), and he answers that it was a snapshot of a movie that creeped him out. So I suspect he made it up. He also has an amusing blog on the subject over here.

I kinda want to buy a garden gnome now. Since my sister also read this, it could "appear" in various places to scare her!

4/5 stars for pure creativity; probably won't buy it, but it was worth a read

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)